Interview with John Poulsen, author of Shakespeare for Readers’ Theatre

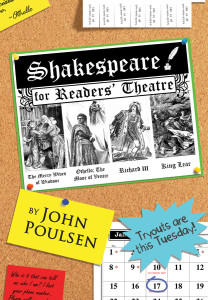

The much anticipated second volume in John Poulsen’s Shakespeare for Readers’ Theatre, releases September 1, 2016, Shakespeare’s Greatest Villains. Poulsen explores the legendary villains from The Merry Wives of Windsor; Othello, the Moor of Venice; Richard III, and King Lear.

Five Rivers’ publisher, Lorina Stephens, interviewed John Poulsen about this forthcoming edition.

LJS: The second volume of Shakespeare for Readers’ Theatre release September 1, 2016. What is the theme of this volume and why did you choose the plays you did?

JP: The theme of the second volume is Villains. Personally I really like villains. They are often under-rated with regard to importance to a story. I believe there is a greater chance of having a successful story with a strong compelling villain, versus a strong compelling protagonist. Ideally a good story wants both. Without a good villain, with clear and selfish motives, there is little to struggle against. Protagonists can become very sappy and weak when dealing with weak villains so that audiences often are just not interested in the story.

A villain should have a strong and interesting personality so that audiences become interested at the beginning. Eventually villains become someone that, on balance, the audience is pleased are being rightfully punished. By the end of Richard III I have a grudging respect for Richard but I agree with the story arc of him being killed.

Strong villains means that the protagonist can be flawed/interesting and still sit on the side of right. A strong villain often makes the story interesting from early on as there is often an audience connection to the story.

Iago is strong from the beginning. I personally know people who are somewhat like Iago but nowhere as extreme – Iago-light, and they are interesting to me. Iago-light people are compelling in that they are funny, charming and smart. But their lack of empathy and kindness make them dangerous, so hanging out with them is very edgy. Inevitably I tend not to hang out with them much because of the net social loss on my part. My gains in hanging out with Iago-lites are laughter and insight. My losses are a feeling of laughing at the wrong things and getting insights that are mean and demeaning. I also do not like having a constant sense that when I hang out with Iago-light people that I become a bit like a Roderigo and I will be the next target of Iago-light’s sharpness or machination.

Having a connection to Iago quickly because of my past pulled me into the play.

The other interesting thing is that many Shakespearean villains straight up admit, or glory in, their villain-hood. Richard III says he wants to be a villain. Edmund, in Lear, essentially says the same thing. And they make sense to me. Yes, if you have been unfairly punished at birth with deformities or unfairness there should be a reckoning. I, for example, have to wear glasses. There is a small part of me that is envious of people with perfect eyesight and that part can be inflamed by the likes of Richard or Edmund. Watching the play then lets me see where my being incensed could take me. That is, my sense that I should have everything everybody else has is based in entitlement. If my entitlement is let run rampant then I step into the realm of Richard and Edmund. By hearing them justify their actions and then seeing their consequences. I can use their experience to make me a better person.

LJS: Are there any new formats or features in this volume which didn’t appear in Volume 1?

JP: Yes, a new element in this volume is suggested casting. Giving the abridged plays to students without casting suggestions makes it very difficult for a director/teacher to be flexible with regard to allocation roles. Without the casting suggestions, often readers are allocated roles oddly. For example, a reader playing King Lear could also be asked to play Kent. The odd situation could occur that the reader would have to speak to his or herself. That is, she/he would have to read both sides of a conversation. Some experienced actors could make this work, but skill is required.

Having suggested casts available allows the teacher/director to change casts quickly and efficiently.

For example, lets assume that the teacher decides that the students will work on the 45 minute King Lear and has 26 copies of the script on hand for the 26 students in the class. The teacher has looked at the casting suggestions and decides to go with the suggested casting on pages 279-284. At the top of the class she/he hands scripts to the students as they enter the room and puts them into two groups: section 1 and section 2. At the beginning of class, the teacher sees that there are 20 students in class. He/she explains that each group will be performing either section one or section two. Each group is responsible for allocating roles and reading through the script with the proviso that consideration be given to allocating the heavier roles to more competent readers. The teacher will also explain that as students come in late they will be added to the groups and changes will have to be made. Attention will be drawn to the casting suggestions on pages 279-284.

The students then will count the number in each group and then look at the suggested casts. For example, with 20 students in the class at the bell, then section one group should have 10 readers and section two group should also have 10 readers. The suggested roles are outlined. Good readers could volunteer for the heavier roles such as King Lear. More timid performers might want Goneril or Cornwall.

If suddenly three students enter late, then the teacher and each group would have to look at the casting suggestions for 23 students. The teacher would allocate one student to group section 1 and two students to group section 2. The groups would then look at casting suggestions for 23 students and change accordingly. Within group section 1, reader 8 would have to give up one or two of the three parts he/she was reading. Reader 8, when there were 20 students, was reading the parts of King of France, Edgar and Oswald. With the addition of a group member he/she could chose to take the part of Reader 9 (King of France and Edgar) or Reader 11 (Oswald).

Group section 2 would have two new group members. Reader four would have to give up one of his characters, Edmund or Oswald, to one of the newly arrived group members. Reader 7 would also have to give up some of his/her three characters. Reader 7 could be either Albany or Cornwall and Captain. This inserting of new readers could be done right up to the time of presentation allowing even very late students to have a chance to read.

The purpose of the casting suggestions is to allow the leader of the group of readers to make quick decisions regarding casting as well as being flexible right up to performance. It also makes sure that double/triple casting is done so that readers do not have characters that speak to one another.

LJS: Who would find Shakespeare for Readers’ Theatre of interest or value?

JP: This volume is intended for teachers/instructors/directors of individuals above the age of 13. I have used this successfully with children younger than this but the work beforehand needs to be more extensive. With older students the scripts themselves become instructive. That is, as the students work with the language and story, both become clearer and the students’ understanding increases with only minimal frustration. This frustration comes often in the form of “why didn’t Shakespeare just say it clearly like….” This is a common sentiment that I have heard often, and it usually precedes readers’ learning. That is, often after being asked this question I will hear the same student explain the reason for Shakespeare’s language such as, “Shakespeare was a poet so he didn’t speak plainly because he wanted to paint with words.”

LJS: You’ve invested considerable time and effort over the years bringing Shakespeare to your students and the public in general. What’s your passion with Shakespeare?

JP: I am one of those who believe that Shakespeare is the greatest playwright and possibly the greatest writer in the English language. I like plays and I find looking at depth into Shakespeare’s work gives me joy. Just the same as someone who really likes hockey might really delve into the life and work of Gretsky or Howe. Experiencing the best in a particular field brings intrinsic joy, be it painting, welding, or gardening. If you are a welder or just enjoy welding, seeing a master at work is beautiful. A fine weld to an expert can be a thing of beauty, satisfying and intrinsically good. Same with me, I truly enjoy experiencing Shakespeare’s literary journeys that he has taken me on.

LJS: There’s to be another volume in the next year or two. Where do you plan on going with that?

JP: The next volume will look at Shakespeare’s women. I have heard and read that Shakespeare was (1) a terrible writer for women and (2) a brilliant writer for women. More often have I heard that he was the first writer to create exciting roles for women whereby the women have strong and interesting personalities. I like how he portrays women and I like the range that they have.

I see that range in the form of a desire/reality conflict. A good example is Lady Macbeth. Lady Macbeth is driven to get and keep power – her desire. However, the reality is that Lady Macbeth’s opposing flaw to gaining absolute power is that she overreaches what inhumane things she can do and still stay sane. He desire to gain power is not matched with her ability to be Machiavellian.

Volume three will examine four plays that feature strong women: Antony and Cleopatra, Macbeth, As You Like It, and Much Ado About Nothing.

Shakespeare for Readers’ Theatre, Book 2: Shakespeare’s Greatest Villains, will be available September 1, 2016, in both print and eBook formats, directly from Five Rivers and online booksellers worldwide.

Shakespeare for Readers’ Theatre, Book 2: Shakespeare’s Greatest Villains, will be available September 1, 2016, in both print and eBook formats, directly from Five Rivers and online booksellers worldwide.

Trade paperback 7 x 10, 524 pages, $64.99

eBook, $9.99