D.G. Laderoute talks about The Great Sky

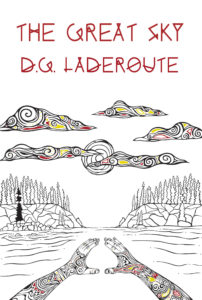

D.G. Laderoute talks with publisher, Lorina Stephens, about his new YA novel, The Great Sky.

LJS: Your second YA novel, The Great Sky, releases October 1. Can you tell us about the story and what inspired you to write it?

DGL: The Great Sky revolves around two Aboriginal Canadian boys, Piper and his cousin Oliver. The story opens with both of them as kids, ten years old. Piper has a near-fatal accident in the bush near his home on a remote reservation (the “rez”), but is saved by the intervention of a strange, otherworldly force. The story then moves forward six years; both Piper and Oliver are now attending high school in a large city, which is quite a culture shock for two young men who had spent their lives up to that point living on the isolated rez. Piper and Oliver both deal with this upheaval in their lives in different ways—Piper keeps himself apart and reclusive, while Oliver falls in with a street gang of other, disaffected Aboriginal youths. It’s into this difficult time in their lives that the enigmatic “otherworld” again intrudes. Piper and Oliver soon both find themselves in the thick of a conflict being fought in the “spirit world”, a parallel realm that darkly mirrors our own. The two cousins, who grew up as best friends, are pulled to opposite sides of this conflict, ultimately pitting them against one another. Thematically, The Great Sky is about friendship, loyalty and love, the things that test them, and to what lengths people will go to either preserve or betray them.

I can point to two sources for inspiration for The Great Sky. The first is the Ojibway (or Anishnabek) people themselves. In my professional career, I had occasion to work closely with many Anishnabek people and communities, and came to admire and respect them. They retain a rich and nuanced culture, which I began to explore in my first book, Out of Time. The Great Sky seemed like a logical continuation to that exploration. However, where Out of Time focused mostly on the traditional culture of the Ojibway people—my Ojibway protagonist in that book, Gathering Cloud, being from pre-European-contact North America—The Great Sky addresses the more complex, and frankly somewhat more difficult blending of traditional and modern cultures.

My second inspiration is from a somewhat different sort of storytelling with which I’ve been involved for many years—that of role-playing games. One such game in particular, called World of Darkness, includes a spirit world that is a twisted and often dark reflection of our own world. I always found the concept of this fascinating—and I’m apparently not the only the one! If you’ve seen the recent hit series on Netflix called Stranger Things, you’ll know that it involves a dark mirror of our world called “the Upside-Down”. The idea that a sinister mirror of our world might exist just a step away (literally, in the case of The Great Sky) was just too good a storytelling opportunity to pass up.

LJS: You seem to be drawn to Anishinabek culture. What is it about the culture that captures you?

DGL: A good question, since my debut novel, Out of Time, and this new one, The Great Sky, both prominently feature Anishnabek culture. I guess what fascinates me about it is the way in which the Anishnabek culture and beliefs so thoroughly and seamlessly incorporate spiritual belief into the “real” world. The spirits of Ojibway folklore reflect the things that were important to their traditional, hunter-gatherer society. For instance, each animal is represented by a somewhat idealized spiritual version, which epitomizes that animal’s behavior and role in nature. Less tangible phenomena, like storms and seasons, likewise have their spirit representations; thunder, lightning and wind are, for example, epitomized by Animikii, the Thunderbird. Even human behavior is reflected in the spirit-world, an obvious example being Wendigo, a dark and dangerous spirit that represents hunger, excess and cannibalism—a dire, but sometimes real thing among people who had to last out long winters with only the food they could hunt and gather.

As a scientist (I have a Master of Science degree in Geology and Geochemistry), I understand the scientific explanation of how the world was formed and how it works. The Anishnabek beliefs, in their own way, do an equally good job of explaining the world, and in a way that puts people much more at the center of things, linked to and reliant upon the other components of the world, animal, vegetable and mineral. I think it’s this very human and holistic belief system that I find so compelling as a story-teller.

LJS: In the novel you also deal with gang culture. You were a Lieutenant Colonel in the Canadian Army Reserves. Did that background inform your handling of how two of your characters, Piper and Oliver, interacted and responded to their peers and their environment?

DGL: It did, in a couple of ways. First, the military is a hierarchy, up which (generally) one advances because of their achievements, and in which any given level (again, generally) exercises rigorous authority and discipline over those subordinate. This relatively rigid, meritocratic and authoritative environment also applies to gangs…although I hasten to add that I don’t consider the military and gangs to be equivalent! For example, a promotion in the military and promotion in a street gang tend to follow two very different paths. I did a great deal of research into gangs and that informed me about the facts, but the mindset of superior-subordinate, following orders, having varying degrees of respect for those above and below you, etc. was very helpful in bringing a “spark of life” to the gangs in The Great Sky…or, at least, I hope so, but that will be for the readers to judge!

The other aspect of my military experience that was helpful was conflict resolution. The military is, by its nature, about violence applied to problems—and again, so too are gangs. But it’s also about brotherhood, and camaraderie, and standing by your friends and colleagues when they need you. Again, so are gangs. Where the two definitely diverge is in the way in which they handle internal conflict. The military, because of its culture of violence as a tool in accomplishing what it does, needs some very robust internal conflict resolution. We really don’t want soldiers to work out their issues with weapons! This is less true for gangs, in which application of strength and power are commonly the way in which disputes are resolved. I wanted Oliver, the character who ends up involved with a gang in The Great Sky, to actually bring a more “military” form of thinking to the gang, in part because of his own attributes and values, and in part because of a way in which he’s being influenced (and I’ll leave that particular point there, because I don’t want to give too much away). He’s determined to focus the gang on its brotherhood, its sense of belonging, to a group of young aboriginal people who are otherwise missing these things in a big, cold city. He doesn’t want its culture of violence to be the “go to” for every problem and issue they encounter. And when violence IS required, he wants it to be focused, purposeful and as brief and limited as possible. This ends up creating both opportunities and problems for him and his fellow gang-members…which is kind of the point!

LJS: There are those who would say you’re appropriating Anishinabek culture. How do you respond to that?

DGL: This is a very real concern for writers. In fact, I sat on a panel at When Words Collide 2016, a major Canadian writing conference in Calgary, about this very thing. The fact is that, unless every writer crafts nothing but what amounts to an autobiography, we are always going to be treading into the “space” of other people and cultures. I’ve written female protagonists, but I’m not a woman; I’ve written stories from the perspective of street kids, but I’ve never been homeless. What it comes down to, I think, is that when a writer creates a story that is outside his or her own experience and surrounding culture, he or she has an obligation to be sensitive in how its portrayed. This means doing the work to understand the people and their culture, so it can be portrayed accurately and respectfully. I did a great deal of research before embarking on writing The Great Sky, speaking to Ojibway people I know and having them act as “alpha” readers, mining the Internet for information (while being wary of the accuracy of stuff on the Internet!) and consulting primary sources. Foremost among the latter is the work of the late Basil Johnston, a renowned Ojibway scholar and folklorist. Likewise, since once of the characters, Oliver, ends up in a street-gang in The Great Sky, I did a lot of research into gangs in general and Aboriginal gangs in Canada in particular. Gang culture is another sort of culture and, while obviously really controversial, it still needed to be something I understood and could write about realistically.

Now, did I get everything right? Probably not. I think, though, as long as the writer makes a serious and good-faith effort to be sensitive, accurate and respectful, it’s possible to write across the boundaries of race, culture, gender, sexual orientation and so on. Of course, it’s ultimately up to the reader to pass judgment!

LJS: There is something of Charles de Lint in your work, that sense of the spirit world co-existing with ours, of stepping sideways into an alternate reality. Has de Lint been an influence on your work? Or is that sense of the spirit world something which fascinates and draws you?

DGL: I think I’ve read just about everything Charles de Lint has written; yes, I love his work. It goes without saying that he’s been a definite influence on me. However, the concept of a spirit world that parallels ours is something that’s intrigued me since I first read books like The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis or The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant by Stephen Donaldson. In both those cases, the “otherworlds” aren’t strictly parallel, but they act as mirrors for events in the characters’ own “real” worlds. It was when I was introduced to the World of Darkness role-playing game, as I mentioned previously, that the idea really crystallized for me. Traditional Ojibway beliefs prominently feature a spirit world that overlaps with ours; World of Darkness explicitly describes a spirit realm that mirrors our own, mortal world. And my other major writing endeavor, that of the Legend of the Five Rings game setting, likewise draws on Asian (predominantly Japanese) myths and legends about the residence of spirits, or kami, in essentially every aspect of our world. Put all of this together and it’s a really compelling idea—that there is more to our world than the physical concepts of space, time, matter and energy. I think every culture has struggled with explaining that thing called “the spark of life”—that is, whatever it is that takes dumb matter and imbues it with thought and emotion.

Now, I certainly don’t profess to have the answer for that, one of the biggest questions of all time! But the existence of a world of spirits, that exists alongside ours and occasionally laps up against it, and sometimes intrudes into it, is a really fascinating possibility.

LJS: You use a fascinating phrase in The Great Sky, where Piper describes entering the spirit world by digging down. Why that phrase?

DGL: Piper comes to describe it this way thanks to a group of characters who call themselves the “Worms”. They’re all capable of moving between our world and the spirit world, essentially at will, and have come to think of this as “digging”. They see themselves as similar to earthworms, burrowing through the earth, sometimes coming to the surface. From their perspective, the real world is…well, the real world, while the spirit world is the “Dirt”, into which they can “dig”. Piper ends up interacting with the Worms, and soon comes to use their lingo regarding the two worlds and moving between them.

There is, however, a bit of an ulterior motive here. By referring to the spirit world as “the Dirt”, the Worms—and Piper—are automatically creating a hierarchy the worlds, implying that the spirit world is somehow beneath, or lesser than, the real world. Calling the spirit world “the Dirt” should sound somewhat disrespectful, because it is. Since I’m planning a sequel to The Great Sky (I’m working on it now, in fact), I intend to bring this bit of conceit back and throw it in their faces. Their implicit and somewhat contemptuous dismissal of the spirit world as somehow ranking below the mortal one will be something they soon come to regret!

LJS: You also write for role-playing games. How different, or similar is writing a novel to writing a story arc for an RPG?

DGL: It’s very different, actually. A novel is a collaborative effort between writer, editor, publisher and reader, but role-playing games tend to involve many more people, in a “shared world” sort of way. Not only do there tend to be multiple writers contributing to a role playing game, there are also game designers developing the mechanical aspects of the game (the parts of the game in which players role dice, consult tables, etc.). Moreover, a role playing game is a different sort of product than a novel, so it gets manufactured, marketed, distributed and sold differently.

All that said, though, there is some commonality. Both a novel and a role playing game ultimately have to involve a compelling story about believable, relatable characters facing difficult situations and hard choices. So, while the general principles of storytelling are applicable to both, the actual writing of each is quite different. Taking Legend of the Five Rings as an example, a great deal of effort went into the storytelling aspect of the game, as its world, the land called Rokugan, involved many, many characters immersed in decades of political intrigue, magical strife and outright war (in fact, the sheer volume of story-telling behind Legend of the Five Rings dwarfs even George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (aka A Game of Thrones!) Since it was based on predominantly Japanese folklore, it incorporated a lot of what we refer to as “samurai drama”—that is, a lot of struggle and, ultimately, sacrifice of oneself for a greater good. I was only one writer of many who contributed to this body of work, and all of that writing was done, in the end, to support and service the game products set in the world of Rokugan.

The Great Sky, by D. G. Laderoute, is available in both print and eBook from Five Rivers, select bookstores, and online booksellers worldwide.