Michelle Enzinas talks about forthcoming book: Big Buttes Book

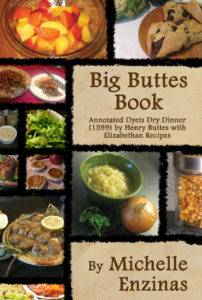

Historical re-enactor and experimental archeologist Michelle Enzinas chatted with publisher and editor, Lorina Stephens, about her forthcoming, stunning debut book, Big Buttes Book: Annotated Dyets Dry Dinner (1599), by Henry Buttes, with Elizabethan Recipes.

Huge title. Huge book. Amazing information.

LJS: Over 230 images and recipes, an analysis of Henry Buttes’ dry dinner presentation – whatever possessed you to undertake such a massive project?

ME: I was excited to explore the food in a single body of work. I wanted to really understand this particular culinary moment in time. In the beginning, I also had no idea it was going to be such a massive project. I learned a lot which is awesome.

LJS: What is it about the Elizabethan/Tudor era that attracts you?

ME: I like that there is such a wealth of material available to study. There are many extant pieces of pottery and other artifacts still in existence. There are hundreds of beautiful cookbooks scanned by museums to read and compare. The English of the Tudor period is similar enough to modern English to still be readable.

The food itself is also attractive. It’s full of flavour, with many spices and different combinations of fats for seasoning. English cooking is considered bland now, but Elizabethan cooks were flush with flavour.

LJS: How did you come across Buttes’ work, and what was it about that particular body of work that fascinated you?

ME: I found the manuscript on Early English Books Online approximately 11 years ago; to be honest, I was probably looking for something else.

Reading Buttes’ work about food, with his funny stories and his bad jokes, really spoke to me. I wanted to try his food combination suggestions, but I wanted to understand his humour even more. It’s so personal across the centuries. The title of the book Big Buttes Book is a tribute to his bad puns and wordplay, and I believe he would have loved it.

LJS: Apparently recreating historic food preparation is a passion of yours. Why food? Why not, say, garment construction, or metalwork, or any of a number of other aspects of experimental archaeology?

ME: I’ve tried many things over the years, but none of them have given me as much pleasure as cooking has.

Cooking is complicated for me. I have a number of food allergies and sensitivities, but they are mostly to New World foods. About 10 years ago I decided that, since I required cookbooks to prepare meals, I would try using historic cookbooks as a source of recipe ideas. I chose to focus on pre-1700 cookbooks since my family is involved in a few different living archaeology and recreation groups.

LJS: Were there surprises in your research?

ME: When I first approached the book I thought it was an herbal medicine guide and a cookbook. I was on my third or fourth pass when I put enough of the story together to realize it was a plan for a dinner party. This was so different from everything I had learned about Tudor feasts that it didn’t occur to me at first that this was a menu. There are so many vegetarian dishes, and no wine; very different than what I had expected.

I learned that many foods are still only available seasonally. I learned that if a cook took the bother to write down a food combination 500 years ago — maybe we should try it before we discount it.

LJS: You actually prepared all these recipes in the book, and rumour has it you actually prepared a private feast for people. How long did that take you, and did you have assistance?

ME: This is true, I did cook a huge feast for my 40th birthday. And I would like to do it again. It was a wonderful way to spend time with my close friends.

I cooked as many dishes from Henry Buttes’ menu as I could. Not all Tudor items are still available. It took around 12 hours to cook and finish eating. I had the help of a close a friend with culinary experience, and many people drifting through the kitchen to chat and wash dishes.

If I did this again today, I would do some of the dishes differently. After three years of research, and many more attempts at perfecting the recipes, some of my interpretations have changed.

LJS: How many of the dishes were tested both in a modern kitchen and in more period conditions?

ME: All the dishes except ‘partridge on a spit’ were tested in a modern kitchen at least once. Most of the dishes were also tested over a fire, with coals, and stewed in clay pots. If my readers have the opportunity to cook with wood fire they really should try it; it adds so much more flavour to everything.

LJS: Were there several tests of each dish, or did you manage to redact them all pretty easily?

ME: Henry Buttes’ core dishes were usually simpler, comfort food style dishes, but some recipes of his, and of the other Elizabethan authors’ I examined, were resistant to easy redaction.

One cheese and anchovy dish took four attempts to get a good ratio of ingredients, but the saffron and cream pie worked perfectly every time. I never did get my eel dish to work well but I suspect that has more to do with the varieties of eels available today, or he simply had more experience cooking them. Buttes’ suggestions for spicing meat are the only way I season those dishes now.

LJS: How were the dishes received? Were your guests seasoned re-enactors with an open palate, or were you dealing with modern tastes?

ME: The dishes were very well received. My guests were all re-enactors, which might have made them more receptive, but the large variety of dishes also allowed each guest to pick foods that were right for their humours, or tastes.

LJS: And so now you have this 516 page hardcover and digital book. Who did you write this for? Who is going to come along and say, “Oh, look, Elizabethan recipes that promote dry humour. Just what I was looking for.”

ME: I am hoping that the Western Martial Arts communities, and The Society for Creative Anachronism, along with other living history groups will use Buttes’ words to broaden the selection of foods served at their events. I hope that people with food restrictions, like vegetarians, can use this book to find more recipes to enjoy. I’m hoping people with a passion for gardening, medieval medicine, and animal husbandry will find this book a reference to further their own research.

ME: I am hoping that the Western Martial Arts communities, and The Society for Creative Anachronism, along with other living history groups will use Buttes’ words to broaden the selection of foods served at their events. I hope that people with food restrictions, like vegetarians, can use this book to find more recipes to enjoy. I’m hoping people with a passion for gardening, medieval medicine, and animal husbandry will find this book a reference to further their own research.

Most of all I wrote this for myself. I want to read this book, and I wanted these recipes in a collection I could refer to.

LJS: After this major undertaking, are you planning on a hiatus for a time, or are you continuing your research into historic food preparation?

ME: I am playing with some ideas for the next book already. I just have to find a title as funny (to me at least) as Big Buttes Book.

Big Buttes Book releases February 1, 2017 in both print and eBook, and is available directly from Five Rivers, and online booksellers worldwide.