Blog Tour with Ira Nayman

Next stop in the blog tour…

… is with fellow author, Ira Nayman.

Ira Nayman is a figment of the imagination of a lawn chair named Francois le Granfalloon. Francois has imagined a rich life for his character Ira featuring the publication of seven novels by Elsewhen Press, the most recent being called Bad Actors. Francois’ creation has been updating a web site of political and social satire, Les Pages aux Folles, for 19 years. In addition to this, imaginary Ira has a PhD in communications from McGill University and was a regular contributor to Creative Screenwriting magazine. Ira was also the editor of Amazing Stories magazine for two and a half years, but Francois is thinking that that may strain credibility, so he may remove it from his imaginings. All of his friends on the patio have urged Francois to write this down before he forgets it, but, being a lawn chair, he doesn’t have the hands to do it…

Taming the Troublesome Trilogy Child

by Ira Nayman

The second novel in a trilogy is always a tricky thing to write. The first book can intrigue the reader with new characters and a new story. The final book can satisfy the reader by bringing the story to a meaningful conclusion. In the middle book, the main characters are not new (although introducing new characters is certainly a strategy) and, although it is possible to conclude subplots, the main plot cannot be resolved (otherwise, your trilogy wouldn’t need a third book).

Tis a dilemma.

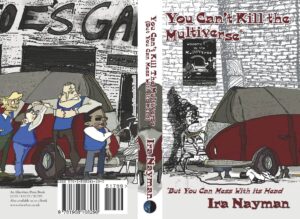

In The Multiverse Trilogy, I have attempted a workaround to the problem of the second novel. But first, a little context: at the end of the second novel in my Transdimensional Authority/Multiverse novel, You Can’t Kill the Multiverse (But You Can Mess With its Head), a madman sets off a device which he believes will destroy the multiverse. Nothing obvious happens. However, Doctor Alhambra, the main scientist of the Transdimensional Authority (the organization which monitors and polices travel between universes) sets up a monitoring system that would set off an alarm should any of the known universes in the multiverse begin to show signs of decay.

At the beginning of Good Intentions, the first book in the trilogy, the alarm goes off. A universe is going to collapse; the only question is when. Unfortunately, the universe contains billions of sentient beings. The diplomatic wing of the Transdimensional Authority hatches a desperate plan to help as many of the beings from that reality settle into other, stable universes as it can.

Good Intentions follows the adventures of the first alien refugee, Rodney Pendleton, as he adjusts to life on Earth Prime (and Earth Prime adjusts to life with Rodney Pendleton). Although there is occasional anti-alien immigrant grumbling and a fair bit of bureaucratic red tape, the first book in the trilogy is generally upbeat, with most human beings Rodney encounters trying their best to help him.

Bad Actors, the second book in the trilogy, takes place two years after the events of the first book, where tens of thousands of alien refugees have immigrated to Earth Prime. Unlike typical second books in a trilogy, Bad Actors does not continue a single story arc started in the first book. Instead, each of its six chapters contains a different storyline, only one of which involves Rodney Pendleton. My intention was for the structure of the novel to reflect the growing diversity of both the alien experience in the new universe and the human responses to the growing alien presence, some of which are quite nasty.

(FLASHFOWARD: In the final book of the trilogy, which has been submitted to my publisher and should be released in 2022, the narrative fractures further, foregoing chapters altogether for a stream of narrative fragments. It is now four years after the discovery of the dying universe, and a million aliens have been relocated to dozens of stable universes; the new narrative structure is meant to mimic the chaos of their experience. It has also occurred to me that the branching narrative over the three books reflects the branching nature of realities in a fractal multiverse. The ending of the trilogy should not come as a surprise to readers – it’s kind of baked into the premise – but I won’t reveal it for fear of being labelled a spoiler spoilsport. All I will say is that while this book continues to explore the darker aspects of the immigrant experience, it does end on a positive note.)

I have treated each book in the series as a stand-alone story, even though characters develop and (as seen by the connection between book two and the first book of the trilogy, which is the sixth book in the series) stories are sometimes connected. Because the trilogy doesn’t have a single story arc, a simple recap can bring the reader up to speed on the current state of the story, allowing the books to be read in any order. For example, The Ugly Truth starts with a Frequently Unasked Questions file that will hopefully set the scene for readers who have not read the previous books while amusing readers that have. (As a humour writer, one of my axioms is “exposition = death,” so I try my best to infuse necessary narrative explanations with comedy.)

(Hey – I may have been a little quick to close that parenthesis. Let me open the parentheses one more time to point out that although I am intellectualizing all over the place in this blog entry, the trilogy is, in fact, humorous. There is wordplay, safes falling from the sky, farts, absurd situations, cows falling from the sky, anvils falling from the sky, raucously witty dialogue, cultural references, breaking of the fourth wall, boulders falling from the sky and, of course, pies. Many, many pies. I wouldn’t want to give you the impression that the trilogy is a dry exercise in formalism.)

I think this fracturing narrative approach serves the Multiverse Refugees Trilogy well; in particular, by introducing new characters and situations, it helps me avoid the perennial problems of the middle child – sorry, I meant middle novel. Granted, it wouldn’t work for most trilogies, with their single story arc, but it would seem to be a fruitful approach for writers who are wiling to play with form.