Blog Tour with Nina Munteanu

The blog tour continues with Nina Munteanu…

…who is a remarkable individual, and someone I highly esteem even though we’ve never met face to face. I came to know Nina through SFCanada.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. The latest in her Alien Guidebook Series—The Ecology of Story: World as Character—is used in schools and universities worldwide. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020. The novel was a finalist for the International Book Award 2021, silver medalist for the Literary Titan Award, Bronze winner of the Foreword Magazine’s ‘Book of the Year 2020’ and longlisted for Miramichi Review’s ‘Very Best Bok of the year award 2020’.

Ten Eco Fiction Novels Worth Reading and Discussing

by Nina Munteanu

In most fiction, environment plays a passive role that lies embedded in stability and an unchanging status quo. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity has consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. This thinking is the ideological manifestation of Holocene stability, remnants from 11,000 years of small variability in temperature and carbon dioxide levels. This stability easily gives rise to deep-seated habits and ideas about the resilience of the natural world.

But this is changing.

Our world is changing. We currently live in a world in which climate change poses a very real existential threat to most life currently on the planet. The new normal is change. And it is within this changing climate that eco-fiction is realizing itself as a literary pursuit worth engaging in.

Eco-Fiction (short for ecological fiction) is a kind of fiction in which the environment—or one aspect of the environment—plays a major role, either as premise or as character. Our part in environmental destruction is often embedded in eco-fiction themes, particularly if they are dystopian or cautionary (which they often are). At the heart of eco-fiction are strong relationships forged between a major character and an aspect of their environment. The environmental aspect may serve as a symbolic connection to theme and can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind; the over-exploited sacred white pine forests for the lost Mi’kmaq in Annie Proulx’s Barkskins; the mystical life-giving sandworms for the beleaguered Fremen of Arrakis in Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Many readers are seeking fiction that addresses environmental issues but explores a successful paradigm shift: fiction that accurately addresses our current issues with intelligence and hope. The power of envisioning a certain future is that the vision enables one to see it as possible.

“the best part about writing science fiction,” says Ottawa SF author Marie Bilodeau, “is showing different ways of being without having your characters struggle to gain rights. Invented worlds can host a social landscape where debated rights in this world – such as gay marriage, abortion and euthanasia – are just a fact of life.” The emerging sub-genre of ‘mundane science fiction’ addresses Bilodeau’s argument by featuring worlds and people within a new paradigm of ‘ordinary’. Eco-fiction examples of ‘mundane’ include Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl and Kim Stanley Robinson’s post-climate-change drowned New York 2140. My novel A Diary in the Age of Water explores a near-future Toronto under severe water scarcity in which the national water utility oversees all aspects of environmental behaviour.

In fact, eco-fiction has been with us for decades—it just hasn’t been overtly recognized as a literary phenomenon until recently and particularly in light of mainstream concern with climate change (hence the recently adopted terms ‘climate fiction’, ‘cli-fi’, and ‘eco-punk’, all of which are eco-fiction). Strong environmental themes and/or eco-fiction characters populate all genres of fiction from the literary fiction of Richard Powers to the speculative fiction of Margaret Atwood and the science fiction of Frank Herbert. This establishes eco-fiction as a cross-genre phenomenon of literature better described as a focus or treatment than a sub-genre or brand, per se. My thought on the emergence of the term eco-fiction to describe works is that we are all awakening—novelists and readers of novels—to our changing environment. We are finally ready to see and portray environment as an interesting character with agency.

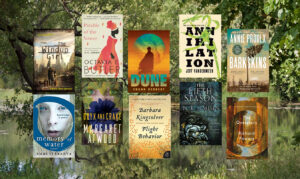

The ten examples I list below of impactful, highly enjoyable works of eco-fiction represent a range of genre, writing style, topic and treatment. Some are optimistic; others are not or have ambiguous endings that require interpretation. The relationship of humanity to environment also differs greatly among these examples as does the role of science. What they all have in common is that they are worth reading and discussing.

Flight Behavior by Barbara Kingsolver (HarperCollins, 2012) is a literary fiction, whose premise of climate change and its effect on the monarch butterfly migration is told through the eyes of Dellarobia Turnbow, a rural housewife, who yearns for meaning in her life. It starts with her scrambling up the forested mountain—slated to be clear cut—behind her eastern Tennessee farmhouse; she is desperate to take flight from her dull and pointless marriage of myopic routine. The first line of Kingsolver’s book reads: “A certain feeling comes from throwing your good life away, and it is one part rapture.” Dellarobia thinks she’s about to throw away her ordinary life by running away with the telephone man. But the rapture she’s about to experience is not from the thrill of truancy; it will come from the intervention of Nature when she witnesses the hill newly aflame with monarch butterflies who have changed their migration behavior.

Flight Behavior is a multi-layered metaphoric study of “flight” in all its iterations: as movement, flow, change, transition, beauty and transcendence. Flight Behavior isn’t so much about climate change and its effects and its continued denial as it is about our perceptions and the actions that rise from them: the motives that drive denial and belief. When Dellarobia questions Cub, her farmer husband, “Why would we believe Johnny Midgeon about something scientific, and not the scientists?” he responds, “Johnny Midgeon gives the weather report.” Kingsolver writes: “and Dellarobia saw her life pass before her eyes, contained in the small enclosure of this logic.”

The Overstory by Richard Powers (W.W. Norton, 2018) is a Pulitzer Prize winning work of literary fiction that follows the life-stories of nine characters and their journey with trees—and ultimately their shared conflict with corporate capitalist America.

Each character draws the archetype of a particular tree: there is Nicholas Hoel’s blighted chestnut that struggles to outlive its destiny; Mimi Ma’s bent mulberry, harbinger of things to come; Patricia Westerford’s marked up marcescent beech tree that sings a unique song; and Olivia Vandergriff’s ‘immortal’ ginko tree that cheats death—to name a few. Like all functional ecosystems, these disparate characters—and their trees—weave into each other’s journey toward a terrible irony. Each in his or her own way battles humanity’s canon of self-serving utility—from shape-shifting Acer saccharum to selfless sacrificing Tachigali versicolor—toward a kind of creative destruction.

At the heart of The Overstory is the pivotal life of botanist Patricia Westerford, who will inspire a movement. Westerford is a shy introvert who discovers that trees communicate, learn, trade goods and services—and have intelligence. When she shares her discovery, she is ridiculed by her peers and loses her position at the university. What follows is a fractal story of destiny, of trees with spirit, soul, and timeless societies—and their human avatars.

Maddaddam Trilogy by Margaret Atwood (McClelland & Stewart, 2013) is a work of speculative dystopian fiction that explores the premise of genetic experimentation and pharmaceutical engineering gone awry. On a larger scale the cautionary trilogy examines where the addiction to vanity, greed, and power may lead. Often sordid and disturbing, the trilogy explores a world where everything from sex to learning translates to power and ownership. Atwood begins the trilogy with Oryx and Crake in which Jimmy, aka Snowman (as in Abominable) lives a somnolent, disconsolate life in a post-apocalyptic world created by a viral pandemic that destroys human civilization. The two remaining books continue the saga with other survivors such as the religious sect God’s Gardeners in The Year of the Flood and the Crakers of Maddaddam.

The entire trilogy is a sharp-edged, dark contemplative essay that plays out like a warped tragedy written by a toked-up Shakespeare. Often sordid and disturbing, the trilogy follows the slow pace of introspection. The dark poetry of Atwood’s smart and edgy slice-of-life commentary is a poignant treatise on our dysfunctional society. Atwood accurately captures a growing zeitgeist that has lost the need for words like honor, integrity, compassion, humility, forgiveness, respect, and love in its vocabulary. And she has projected this trend into an alarmingly probable future. This is subversive eco-fiction at its best.

Dune by Frank Herbert (Penguin Random House, 1965) is a science fiction novel that chronicles the journey of young Paul Atreides, who according to the indigenous Fremen prophesy will eventually bring them freedom from their enslavement by the colonialists—The Harkonens—and allow them to live unfettered on the planet Arrakis, known as Dune. As the title of the book clearly reveals, this story is about place—a harsh desert planet whose 800 kph sandblasting winds could flay your flesh—and the power struggle between those who covet its arcane treasures and those who wish only to live free from slavery.

Dune is just as much about what it lacks (water) as it is about what it contains (desert and spice). The subtle connections of the desert planet with the drama of Dune is most apparent in the actions, language and thoughts of the Imperial ecologist-planetologist, Kynes—who rejects his Imperial duties to “go native.” He is the voice of the desert and, by extension, the voice of its native people, the Fremen. “The highest function of ecology is understanding consequences,” he later thinks to himself as he is dying in the desert, abandoned there without water or protection.

Place—and its powerful symbols of desert, water and spice—lies at the heart of this epic story about taking, giving and sharing. This is nowhere more apparent than in the fate of the immense sandworms, strong archetypes of Nature—large and graceful creatures whose movements in the vast desert sands resemble the elegant whales of our oceans.

Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer (HarperCollins, 2014) is a science fiction eco-thriller that explores humanity’s impulse to self-destruct within a natural world of living ‘alien’ profusion.

The first of the Southern Reach Trilogy, Annihilation follows four women scientists who journey across a strange barrier into Area X—a region that mysteriously appeared on a marshy coastline and associated with inexplicable anomalies and disappearances. The area was closed to the public for decades by a shadowy government that is studying it. Previous expeditions resulted in traumas, suicides or aggressive cancers of those who managed to return.

What follows is a bizarre exploration of how our own mutating mental states and self-destructive tendencies reflect a larger paradigm of creative-destruction—a hallmark of ecological succession, change, and overall resilience. VanderMeer masters the technique of weaving the bizarre intricacies of ecological relationship, into a meaningful tapestry of powerful interconnection. Bizarre but real biological mechanisms such as epigenetically-fluid DNA drive aspects of the story’s transcendent qualities of destruction and reconstruction.

The book reads like a psychological thriller. The main protagonist desperately seeks answers. When faced with a greater force or intent, she struggles against self-destruction to join and become something more. On one level Annihilation acts as parable to humanity’s cancerous destruction of what is ‘normal’ (through climate change and habitat destruction); on another, it explores how destruction and creation are two sides of a coin.

Barkskins by Annie Proulx (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2016) is a work of literary fiction that chronicles two wood cutters who arrive from the slums of Paris to Canada in 1693 and their descendants over 300 years of deforestation in North America.

The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect for anything indigenous and a fierce hunger for “more” of the forests and lands. Ensnared by settler greed, the Mi’kmaq lose their own culture; their links to the natural world erode with grave consequence.

Proulx weaves generational stories of two settler families into a crucible of terrible greed and tragic irony. The bleak impressions by the immigrants of a harsh environment crawling with pests underlies the combative mindset of the settlers who wish only to conquer and seize what they can of a presumed infinite resource. From the arrival of the Europeans in pristine forest to their destruction under the veil of global warming, Proulx lays out a saga of human-environment interaction and consequence that lingers with the aftertaste of a bitter wine.

Memory of Water by Emmi Itäranta (Harper Collins, 2014) is a work of speculative fiction about a post-climate change world of sea level rise. In this envisioned world, China rules Europe, which includes the Scandinavian Union, occupied by the power state of New Qian. Water is a powerful archetype, whose secret tea masters guard with their lives. One of them is 17-year old Noria Kaitio who is learning to become a tea master from her father. Tea masters alone know the location of hidden water sources, coveted by the new government.

Faced with moral choices that draw their conflict from the tension between love and self-preservation, young Noria must do or do not before the soldiers scrutinizing her make their move. The story unfolds incrementally through place. As with every stroke of an emerging watercolour painting, Itäranta layers in tension with each story-defining description. We sense the tension and unease viscerally, as we immerse ourselves in a dark place of oppression and intrigue. Itäranta’s lyrical narrative follows a deceptively quiet yet tense pace that builds like a slow tide into compelling crisis. Told in the literary fiction style of emotional nuances, Itäranta’s Memory of Water flows with mystery and suspense toward a poignant end.

The Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. Jemison (Orbit, 2018) is a fantasy trilogy set in a far-future Earth devastated by periodic cataclysmic storms known as ‘seasons.’ These apocalyptic events last over generations, remaking the world and its inhabitants each time. Giant floating crystals called Obelisks suggest an advanced prior civilization.

In The Fifth Season, the first book of the trilogy, we are introduced to Essun, an Orogene—a person gifted with the ability to draw magical power from the Earth such as quelling earthquakes. Jemison used the term orogene from the geological term orogeny, which describes the process of mountain-building. Essun was taken from her home as a child and trained brutally at the facility called the Fulcrum. Jemison uses perspective and POV shifts to interweave Essun’s story with that of Damaya, just sent to the Fulcrum, and Syenite, who is about to leave on her first mission.

The second and third books, The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky, carry through Jemison’s treatment of the dangers of marginalization, oppression, and misuse of power. Jemison’s cautionary dystopia explores the consequence of the inhumane profiteering of those who are marginalized and commodified.

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi (Nightshade Books, 2009) is a work of mundane science fiction that occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of predatory ag-biotech multinational giants that have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing genetic manipulations.

The book opens in Bangkok as ag-biotech farangs (foreigners) seek to exploit the secret Thai seedbank with its wealth of genetic material. Emiko is an illegal Japanese “windup” (genetically modified human), owned by a Thai sex club owner, and treated as a sub-human slave. Emiko embarks on a quest to escape her bonds and find her own people in the north. But like Bangkok—protected and trapped by the wall against a sea poised to claim it—Emiko cannot escape who and what she is: a gifted modified human, vilified and feared for the future she brings.

The rivalry between Thailand’s Minister of Trade and Minister of the Environment represents the central conflict of the novel, reflecting the current conflict of neo-liberal promotion of globalization and unaccountable exploitation with the forces of sustainability and environmental protection. Given the setting, both are extreme and there appears no middle ground for a balanced existence using responsible and sustainable means. Emiko, who represents that future, is precariously poised.

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler (Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993) is a science fiction dystopian novel set in 21st century America where civilization has collapsed due to climate change, wealth inequality and greed. Parable of the Sower is both a coming-of-age story and cautionary allegorical tale of race, gender and power. Told through journal entries, the novel follows the life of young Lauren Oya Olamina—cursed with hyperempathy—and her perilous journey to find and create a new home.

When her old home outside L.A. is destroyed and her family murdered, she joins an endless stream of refuges through the chaos of resource and water scarcity. Her survival skills are tested as she navigates a highly politicized battleground between various extremist groups and religious fanatics through a harsh environment of walled enclaves, pyro-addicts, thieves and murderers. What starts as a fight to survive inspires in Lauren a new vision of the world and gives birth to a new faith based on science: Earthseed. Written in 1993, this prescient novel and its sequel Parable of the Talent speak too clearly about the consequences of “making America Great Again.”

A version of this article first appeared on Tor.com in 2020.